2022 Project Study by Naiya Hall, Hokkaido University

Back to homepage

Why the Tokugawa Shogunate Did Not Optimize the Land Tax

Abstract

During the Tokugawa period, the peasants were left with an agricultural surplus after they paid their tribute to the rulers, a surplus which arose due to the growing increases in agricultural yields, and the inaccuracy of the cadastral surveys and lack of resurveying. While many historians reference this surplus as a matter of fact, this paper asks a question that only a few have asked: why did the Tokugawa shogunate allow this surplus and decide not to conduct more accurate surveys to take advantage of increasing agricultural yields? This paper seeks to reveal the shogunate’s position by looking at the environment surrounding the cadastral surveys and observing the shogunate’s other social policies and efforts to manage the rice market. The conclusion reached is that while the shogunate initially allowed a surplus as a safety margin for the peasants in order to further their higher goals of increased productivity, the societal changes and ensuing market complexity over time came to limit their ability to exact more tax, thus the accuracy of the surveys came to be of little difference.

Introduction

In the last century, an interest in the history of the common peoples has resulted in a steady increase of English literature on the peasants of Tokugawa Japan. With historians uncovering more details about the economy and society, the previous idea that peasants lived at near subsistence levels and were taxed harshly came to be challenged by more penetrative studies. As investigation revealed that the amount of the tax was less than it originally appeared, it became evident that the peasants were left with a surplus (Smith 1958). Further research revealed that this surplus was due to the original land surveys being not entirely accurate nor subsequently resurveyed after agricultural improvements increased crop output (Brown 1989, Hayami 2015, Tanimoto 2019). From this research, a question has arisen of why the shogunate did not take steps to improve the accuracy of the land assessments and take advantage of the agricultural production increase (Brown 1989, Smith 1958), as doing so could have relieved the financial pressures of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

This paper seeks to answer this question by contextualizing it within the social policies that were put in place by the Tokugawa shogunate, the observation of which can reflect their overall goals and position towards the peasants. Beginning with a review of the historical data which substantiates the existence of the surplus, the factors that could have been involved in the decision to not conduct more accurate land surveys are carefully examined. First, a close analysis of the survey market reveals both the origin of the surplus as well as the environment that contributed to a lack of interest in more accurate assessments. Next, drawing on research about the Tokugawa economic policies reveals how they focused on incentivizing peasant productivity. Furthermore, looking at the daimyo and shogunate’s connection to the rice market shows their how their finances were tied closely to the quality of their rice and its market price, and not only dependent on the quantity of rice tax received. Finally, examining the tax rate reveals the inability to raise the tribute rate in the latter half of the eighteenth century, the reason for which is likely connected to why more accurate surveys were not conducted.

From this perspective, I argue that the cadastral surveys were not meant to be a depiction of actual yields as much as a reliable marker for taxation as the daimyo consolidated their domains, as pointed out by Nakabayashi et al. (2020). As the warrior class was removed from the farmlands and land rights given to the peasants, the direct control of the ruling class on the lands themselves gradually weakened. At the same time, with the commercialization of agriculture steadily increasing the complexity of the economy, there arose several factors (moneylenders, price and supply of rice at the village level, land rents, etc.) that the daimyo could not control, which meant that the power to tax the village harshly gradually diminished (Sato 1990, Vlastos 1986). As the ruling class began to invest in the profits to be made on the rice market, the shogunate began to focus on maintaining a balanced price of rice, therefore I argue that investment in more accurate land surveys would have held little practical benefit.

The Origins of the Surplus

There are two factors from which the agricultural surplus arose; one is the gradual but significant increase in crop yields that followed the advancement of agricultural methods introduced in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, and the second is the inaccuracy of the cadastral surveys on which the new land tax system was determined.

The first factor for the agricultural surplus was that the crop yield gradually increased with the proliferation of more advanced agricultural tools, the use of fertilizer, and irrigation projects (Rath 2007, Verschuer and Cobcroft 2017). “The estimation of average land productivity of whole domains from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century suggests that rice yield per acre increased from 0.98 koku [176 liters] in 1650 to 1.30 koku [234 liters] in 1850” (Tanimoto 2019, 19). While periodic surveys might have captured this change, from the early eighteenth century onward, only new crops appear to be surveyed (Aratake 2019, Smith 1958). Thus, there arose a growing disparity between the actual yield of crops and their assessed yield, and the tribute rates do not appear to be raised to reflect this change, effectively allowing the villagers to keep the surplus (Hayami 2015, Rath 2007, Yasuba 1986). This increase in agricultural production and subsequent surplus raised the standard of living in Tokugawa Japan (Bornmann and Bornmann 2002) and explains the spread of tenant farming and the increase in rural trade and industry (Rath 2007). Conditions, however, varied significantly between regions and even neighboring farmlands, as the burden of the land tax “ranged widely from 7% to 87%” (Kinoshita 2019, 80). The benefit of the surplus was clearly not equally divided among the peasants and thus led to stratification within the peasant class (Smith 1958, Vlastos 1986).

The second factor for the surplus lies in the cadastral surveys, which were started by Toyotomi Hideyoshi in 1582 and were part of a reorganization of the land tax for the purpose of consolidating the daimyo’s power by clearly separating the classes while preventing rebellion of the samurai and peasants (Totman 2005). The samurai were removed from the farmlands and moved to the castle towns, and the villages became in charge of distributing and collecting the tax burden from the local peasants. This new tax system helped to solidify the sovereignty of the shogunate and daimyo as they became the exclusive receiver of the tax from the peasants of their domain, which increased their finances and allowed for investment in land reclamation to further expand their income. The reason for the assessment inaccuracies stems specifically from the land survey process. Because the surveying was conducted by the domain’s samurai with the help of local peasants, the exact methods varied by locality (Koseki 2015). In addition to this inconsistency, consistently rounding figures down, using imprecise measuring tools (such as hemp rope that would stretch and contract), and a heavy reliance on the surveyor’s estimation introduced significant errors in linear and area measurements (Brown 1989).

While clearly being of great benefit to specific peasants and the overall growth of the economy, the great variance of the survey discrepancies and the increasing agricultural yields meant that the land tax could have been optimized to help ease the growing financial difficulties of the shogunate and daimyo. To uncover why the shogunate did not conduct new cadastral surveys to take advantage of it, it is necessary to look more deeply at the situation surrounding the surveys themselves.

The Surveying Environment

After researching the land surveying techniques in the Tokugawa period, Brown (1989) concluded that the key to understanding why the shogunate did not develop the native triangulation methods or exploit new sophisticated techniques from Europe lies in the circumstances surrounding the market for land surveys. Because there were no stringent survey guidelines, the techniques employed were determined by the samurai of the domain and assisting local peasants, and the overall focus was on timeliness instead of accuracy. This meant there was regional variation in the technique as well as limited movement of surveyors, which resulted in a lack of competition.

In addition, investigation into the survey manuals of the time reveal a disdain for sophisticated mathematics, even though there was an interest in more advanced techniques in other fields, such as map making. The use of more accurate methods in other fields reveals that the issue was not availability, as Brown has argued that by the early seventeenth century more advanced measuring tools and techniques were known to surveyors. Brown therefore concludes that the samurai’s disdain for the practical sciences, the lack of competition, and “the intellectual atmosphere surrounding official procedures such as surveying all contributed to an environment in which there were few incentives to refine mensuration and perfect common land survey techniques” (ibid, 61-62).

The surveying market reveals how little interest there is in increasing the accuracy of surveys, but I would argue that it does not fully explain the underlying reason for that disinterest. To see the larger picture, a review of other economic policies of the shogunate is necessary.

A Broader Perspective of the Tokugawa Changes

Historians such as Brown (1989) and Smith (1958) have treated the growing inaccuracies of the cadastral surveys as something that the shogunate should have wanted to correct, observing how the position of the ruling class was one that took full advantage of the peasants for their own gains. A quote of a Tokugawa official that has often been used to emphasize this stance likened peasants to sesame seeds, because “[t]he more you squeeze them, the more you can extract from them” (as cited in Gordon 2003, 9). This perspective, however, assumes from the outset that the inaccuracies of the surveys were not intentional. While the Confucianist concept of a benevolent ruler may not have been prevalent among the ruling warrior class at this time (Tanimoto 2019), they nevertheless had a vested interest in improving the agricultural productivity of the peasants (Totman 2005). This has been emphasized by economic historians who claim that “the stability of the owner-peasant economy was essential to the shogunate”, explaining that when the lands were surveyed a “safety margin” of around 15% was subtracted from the total (Nakabayashi et al. 2020, 157). The deliberate altering of the numbers would account for “economic factors such as distance from market and special costs of production. This was to make sure that the number would be a reasonable basis for making tax demands on the village” (Roberts 1998, 36). From the perspective of the surplus being intentional, the squeezing of the peasants in practice meant creating an environment that incentivized higher productivity.

This goal of increasing productivity can also be observed in the central element of the new tax system in that it granted property rights to individual peasant families, which would incentivize them to make agricultural improvements. Nakabayashi et al. (2020) claim that “protection of the property rights of farmers came with both stronger incentives, promising increased tax revenues in the long term, and compensation for risk-taking, which in practice meant a reduction in taxes” (ibid, 175). The difference in harvest volatility risk is a key factor, as Nakabayashi et al. point out that the daimyo of developed regions, where peasants were able to weather more risk, granted property rights to the peasant families. However, the daimyo of the “backward regions” with lower productivity and more vulnerability to risk “maintained joint ownership at the village level” (ibid). The tax regulation was thus determined by each daimyo according to the amount of risk that they estimated the peasants of their domain could endure, all in an effort to stabilize and grow agricultural production.

Other endeavors for the purpose of increased output can also be observed in extensive land reclamation, irrigation projects, and the financial systems that allowed the peasant to borrow to invest in fertilizer. To this end the shogunate began to regulate the foreclosure of farmland, by banning and subsequently legalizing foreclosures throughout the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. While these policies might appear to be contradictory, Mandai and Nakabayashi (2018) argue that “the shogunate’s on-off regulation and deregulation depended on its measurement error of peasants’ risk attitude” (ibid, 310). They are, therefore, a reflection of the shogunate’s trial and error as they try to keep the market in balance and provide financial stability for further economic growth.

The Dojima Rice Market

The shogunate’s interest in keeping the financial market in balance can also be seen by how they dealt with the Dojima rice exchange in Osaka. By the mid-seventeenth century, the tax rice of many of the daimyo was shipped to this rice market, where the sale and resale of rice certificates and rice futures caused rice prices to increase. With rice from the Chūgoku, Shikoku, and Kyūshū regions being sold and traded at Dojima, it became the central rice market of Japan and greatly affected the value of rice across the country, for other rice markets looked to the Dojima market for price reference (Takatsuki 2022). As the tax rice was sold here for hard currency, the market directly affected the daimyo and shogunate’s finances.

Because the quality of rice affected what price it could be sold at, the daimyo and shogunate became incentivized to increase the quality control of their rice production. Quality was also a determining factor in the selection of each season’s proxy rice, the rice on which the future trades was based on. In order to have their rice chosen as the market’s proxy rice, the daimyo would go to great lengths to ensure quality control, “the only explanation for which is that the designation increased the price of that domains rice certificates” (ibid, 92). Because of this shift in attention to quality, Takatsuki observes that “[t]he burden imposed by the annual tax must be considered not only in terms of the quantities required but in terms of the quality demanded as well” (ibid, 118). I would argue that this focus on quality is another reason why there was little observed interest in accurately reassessing the land surveys to optimize tax, as it was not survey accuracy but agricultural technique that would improve the quality of rice.

A turn of events in the early eighteenth century highlights how much the rice supply affected the rice market price and consequently the shogunate’s finances. With little land left for reclamation, “less productive lands were being forcibly converted to new paddies” and the tax rate was increased; this meant that the supply of rice on the market increased, which caused the price of rice to fall (ibid, 120). This created a vicious cycle “with falling rice prices spurring the government to raise taxes and develop new rice paddies, but these measures increased the rice supply and accordingly depressed the price of rice” (ibid, 120-121). I argue that this effect explains why the shogunate did not take steps to increase the accuracy of land surveys, as Takatsuki points out, “as with land reclamation, the more ‘squeezing’ [of the peasants] increased the supply of rice on the market, which in turn aggravated the downward pressure on the price of rice” (ibid, 120). This effect appears to be well noted by both the market participants and the shogunate, and after the falling rice prices in the early eighteenth century, the daimyo and shogunate alike sought to lower their dependence on tax rice, and other crops began to emerge.

Clearly the relationship of tax rice to actual income was not as simple as just increasing the tax rate, because the amount of hard currency that could be gained was determined by the price at which they could sell their tax rice, a price that would fall if the supply of rice was increased. From these observations, what came to be of prominent importance to the shogunate was ensuring that the price of rice remained in a desirable state, neither too high nor too low in relation to other goods. Keeping in mind how important the balance of the market was to the shogunate, next is an examination of the tax rate itself.

The Stagnation of the Tribute Rate

As conducting new surveys of the land would affect the amount of tax rice required from the peasants, examining the patterns of levied tax throughout the Tokugawa period can enlighten why resurveying was not conducted.

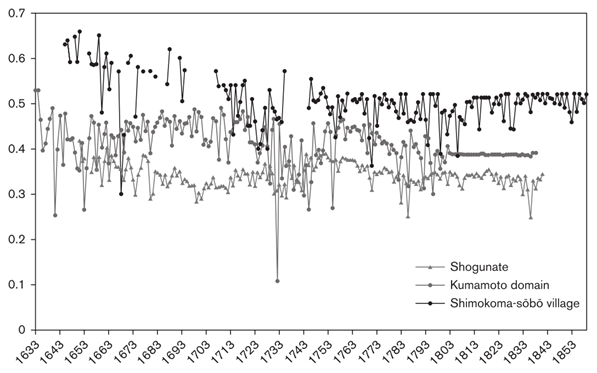

Figure 1 shows the tribute rate from the early seventeenth century until the mid-nineteenth century. The two gray lines represent the average tribute rates recorded from villages in the shogunate and Kumamoto domains, and the black line represents a village in Yamashiro province in western Honshu. While the higher rate of the seventeenth century shows significant fluctuations, from the latter half of the eighteenth century the tribute rates begin to stagnate. At this point in time, the assessed agricultural yield was no longer equivalent to actual yields, therefore “these figures should be taken as a ‘nominal’ index for measuring the distribution of the economic value between rulers and peasants” (Tanimoto 2019, 19). Nevertheless, the lack of tax rate increases is apparent in the latter half of the Tokugawa period.

Figure 1: The Changing Patterns of “Tribute Rate”: Shogunate, Domain, Village

Source: Tanimoto 2019, p. 18.

Reasons for this stagnation has been linked to the rate of peasants’ uprisings, as Furushima (1981) has argued that the peasants’ protests had a slow but lasting effect in preventing the land tax from rising; “if tax trends arc studied on a long-term basis, one can conclude that these insurrections were a great success in resisting the feudal lords” (ibid, 273). Though the increase in protests might coincide with the tribute rate stagnation, Totman (2005) has argued that while the grievances from the seventeenth century were “commonly related to a village’s total tax burden, […] later ones dwelt more on charges of corruption by village officials, burdensome corvée duties, or inequitable allocation of tax obligations or of use rights in woodland and irrigation systems” (ibid, 281). Therefore, they were not a direct result of the amount of levied tax decided by the daimyo and shogunate. “[B]y the late Tokugawa period the intensity of conflict within villages and between the various strata of the peasant class superseded conflict between ruler and ruled” (Vlastos 1986, 159). I would argue that it is this change in social structure that started at the beginning of the Tokugawa period that is the underlying reason for the stagnation of the tribute rate observed in the latter half of the eighteenth century.

A pivotal point in these social changes was the removal of the samurai from the rural areas, which meant that the village became self-managed, an effect that is emphasized by Vlastos. Even though the new tax system initially proved to be an efficient method of taxation, the daimyo did not directly manage the farmland; it was the peasants who individually and communally had control of the factors of agricultural production, thus the actual power of the daimyo as claimants became limited. “[A]fter the development of markets and commodity production, the daimyo found it increasingly difficult to tax at the old rates” (ibid, 10). It is likely, therefore, that reassessing the land for a more accurate survey and optimized tax would have been equally difficult. In addition, in light of the aforementioned rice market policies, the focus appears to be less of exacting every bit of tax rice available and more of managing a healthy rice market in order to maximize the financial gains from the tax rice received.

Conclusion

The ability of the peasants to retain a surplus had a profound effect on the Tokugawa economy; it allowed them to both raise their standard of living and increase agricultural productivity, as profits from yields soon “encouraged the introduction of new techniques to raise the production of goods to satisfy social needs” (Furushima 1981, 274), which in turn directly increased rural trade and industry. This increase in production helped to bring about the commercialization of agriculture and has been argued to be the key to the economic progress observed in the Tokugawa period (Hanley and Yamamura 1977). There is an “almost universal importance of having a substantial and reliable agricultural surplus as the basis for launching and sustaining economic growth” (Nicholls 1963, 28). While the benefit of this surplus is easily seen in hindsight, whether the Tokugawa shogunate was able to realize the potential benefits of allowing the peasants such a surplus may be uncertain; though, if the inaccuracies of the original surveys were meant to be a margin of safety, then perhaps they were not entirely unaware. However, many historians have commented that the intent of the shogunate in how they dealt with the peasants was not necessarily benevolent, with the “squeezing” of the peasants for their own interests (Gordon 2003, Takatsuki 2022). Assuming that to be the case then, something must have been preventing them to take the steps necessary to take advantage of the growing agricultural surplus.

One argument for lack of resurveying is that the extensive manpower required to survey all of the farmland of Japan would be very expensive, and therefore many of them could only be conducted once (Aratake 2019). Other historians, however, have pointed out that the gains to be made by resurveying could have balanced that cost out (Brown 1989, Smith 1958). In addition, Koseki (2015) has noted how “[i]n most cases, local communities also had to shoulder the expense for materials, tools, and hired laborers to conduct the surveys” (ibid, 526). The expense argument, therefore, lacks credibility.

While Brown (1989) has made a strong point in that the environment surrounding surveying and the depreciation of practical sciences were a large factor in the lack of interest in resurveying, I would argue that this is but a reaction to the underlying reason. The end goal of these surveys was increasing the tax rice received, but as the examination of the Dojima rice market revealed, there were clearly many factors which affected the end result of the shogunate’s finances, not just the tax rate. Because the goal of the shogunate appears to have been to keep the price of rice in a healthy balance in relation to the costs of other goods, simply increasing the rice supply by optimizing the land survey would not have been to their advantage, as the amount of rice on the market had a direct effect on the price of rice.

In addition, the leeway given in the original land surveys was meant to be a margin of safety for the peasants against the risk that came with the new tax system, thus, the surveys did not need to be completely accurate. While this margin of safety was successful in increasing productivity, by the time agricultural yields had increased to a level where tax optimization might have been easily viable, the direct control of the peasant class was weakened and exploiting the Dojima rice market and other agricultural and land investments held more viable and lucrative benefits. With an increasingly complex economy, the accuracy of the survey came to have little effect, especially in a time when the rulers seemed to have trouble increasing the tax rate itself. I would argue, therefore, that the reason for the shogunate’s disregard for more accurate surveys lies in their interest in increasing peasant productivity and maintaining a balanced rice market.

Bibliography

Aratake, Kenichiro. 2019. ‘Samurai and Peasants in the Civil Administration of Early Modern Japan’. In Public Goods Provision in the Early Modern Economy, edited by Masayuki Tanimoto and R. Bin Wong, 1st ed., 38–56. Comparative Perspectives from Japan, China, and Europe. University of California Press.

Bornmann, Gregory M, and Carl M Bornmann. 2002. ‘Tokugawa Law: How It Contributed to the Economic Success of Japan’. Journal of Kibi International University: School of International and Industrial Studies 12: 187–202.

Brown, Philip C. 1989. ‘Never the Twain Shall Meet: European Land Survey Techniques in Tokugawa Japan’. Chinese Science 9: 53–79.

Furushima, Toshio. 1981. ‘Economic Conditions for Broadening the Geographical Horizon of Peasant Awareness in the Edo Era’. In Peasantry and National Integration, edited by Celma Agüero, 1st ed., 271–76. Colegio de Mexico.

Gordon, Andrew. 2003. A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present. Oxford University Press.

Hanley, Susan B., and Kozo Yamamura. 1977. Economic and Demographic Change in Preindustrial Japan, 1600-1868. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hayami, Akira. 2015. Japan’s Industrious Revolution: Economic and Social Transformations in the Early Modern Period. Studies in Economic History. Tokyo: Springer Japan.

Kinoshita, Mitsuo. 2019. ‘Sanctions, Targetism, and Village Autonomy: Poor Relief in Early Modern Rural Japan’. In Public Goods Provision in the Early Modern Economy, edited by Masayuki Tanimoto and R. Bin Wong, 1st ed., 78–99. Comparative Perspectives from Japan, China, and Europe. University of California Press.

Koseki, Daiju. 2015. ‘Japanese Cadastral Mapping in an East Asian Perspective, 1872-1915’. Japanese Journal of Human Geography 67 (6): 524–40.

Mandai, Yu, and Masaki Nakabayashi. 2018. ‘Stabilize the Peasant Economy: Governance of Foreclosure by the Shogunate’. Journal of Policy Modeling 40 (2): 305–27.

Nakabayashi, Masaki, Kyoji Fukao, Masanori Takashima, and Naofumi Nakamura. 2020. ‘Property Systems and Economic Growth in Japan, 730–1874’. Social Science Japan Journal 23 (2): 147–84.

Nicholls, William H. 1963. ‘An “Agricultural Surplus” as a Factor in Economic Development’. Journal of Political Economy 71 (1): 1–29.

Rath, Eric C. 2007. ‘Rural Japan and Agriculture’. In A Companion to Japanese History, 477–92. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

Roberts, Luke S. 1998. Mercantilism in a Japanese Domain: The Merchant Origins of Economic Nationalism in 18th-Century Tosa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sato, Tsuneo. 1990. ‘Tokugawa Villages and Agriculture’. In Tokugawa Japan: The Social and Economic Antecedents of Modern Japan, translated by Mikiso Hane, 37–80. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Smith, Thomas C. 1958. ‘The Land Tax in the Tokugawa Period’. The Journal of Asian Studies 18 (1): 3–19.

Takatsuki, Yasuo. 2022. The Dojima Rice Exchange: From Rice Trading to Index Futures Trading in Edo-period Japan. Translated by Rubinfien Louisa. Tokyo: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture.

Tanimoto, Masayuki. 2019. ‘From “Feudal” Lords to Local Notables: The Role of Regional Society in Public Goods Provision from Early Modern to Modern Japan’. In Public Goods Provision in the Early Modern Economy, edited by Masayuki Tanimoto and R. Bin Wong, 1st ed., 17–37. Comparative Perspectives from Japan, China, and Europe. University of California Press.

Totman, Conrad. 2005. A History of Japan. 2nd ed. The Blackwell History of the World. Malden, Mass: Blackwell Pub.

Verschuer, Charlotte, and Wendy Cobcroft. 2017. Rice, Agriculture, and the Food Supply in Premodern Japan. New York: Routledge.

Vlastos, Stephen. 1986. Peasant Protests and Uprisings in Tokugawa Japan. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Yasuba, Yasukichi. 1986. ‘Standard of Living in Japan Before Industrialization: From What Level Did Japan Begin? A Comment’. The Journal of Economic History 46 (1): 217–24.